Violence Intervention Program

What Is VIP?

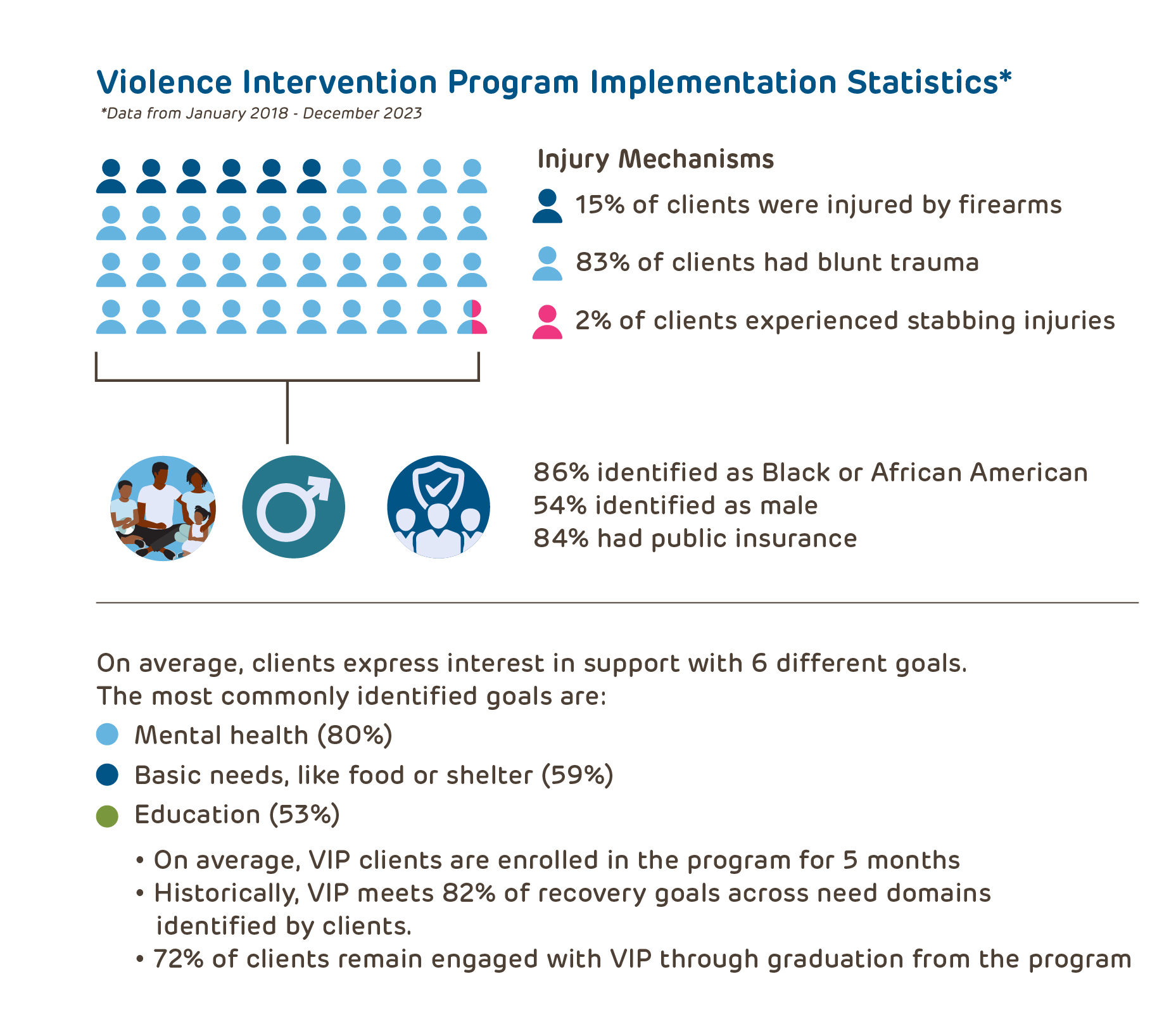

The Violence Intervention Program (VIP) is a community- and family-focused model that provides trauma-informed, intensive case management to youth between 8 and 18 years old who are treated at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for an injury due to interpersonal, community violence. VIP partners with families for 3-6 months to help youth and their families recover, reestablish safety, and navigate systems, including legal, mental health, medical, education, and employment, after a violent event.

Each year, CHOP’s Emergency Department (ED) and Trauma Unit treat approximately 500 patients with assault-related injuries. While many patients leave with their acute medical needs resolved, they and their families often require on-going support to fully recover—physically, mentally, and emotionally. VIP was established in 2012 to go beyond healing physical wounds and bring a public health and trauma-informed care approach to treating assault-injured youth.

Who Are We?

VIP's multidisciplinary team includes clinical, research, and evaluation experts from social work, medicine, psychiatry, psychology, and public health to meet the diverse needs VIP youth and families identify, measure our impact, and disseminate our evidence-based practices. VIP partners with community organizations and individuals across Philadelphia to ensure that families are connected to care and resources that extend beyond their time in VIP.

How Does VIP Work?

VIP staff identify youth treated in the CHOP ED, Trauma Unit, or Concussion Clinic for an injury related to community violence to offer support through VIP. VIP not only serves the assault-injured youth but wraps services around the entire family, including caregivers and siblings, understanding that violence and trauma impact the entire family.

Once enrolled, youth and their families are assigned a case manager, who conducts an intake assessment to learn more about the family’s unique recovery needs. Needs commonly occur within 12 domains, ranging from medical needs to basic needs, such as housing and food insecurity, and can be identified at any time from the intake visit to program graduation.

Access the full suite of activity maps here.

Violence Prevention Specialists provide wrap around care to the whole family, including but not limited to:

- psychoeducation regarding trauma symptoms

- safety planning for community violence or mental health concerns

- connection to resources to support families through the post-injury period

- warm handoff to mental health providers for trauma focused therapy

- advocacy with local agencies, such as housing authorities or the legal system

- navigation through complex systems of care, such as medical follow-up or educational support

How Is VIP A Leader In Hospital-Based Violence Intervention?

CHOP’s VIP is one of more than 60 member programs in The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention (The HAVI), and we are recognized as a model in pediatric hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs). As a HAVI member program, VIP collaborates on clinical best practices, workforce development, and research scholarship to identify opportunities to evaluate, inform, and disseminate HVIP best practices, particularly to new and emerging pediatric programs.

Measuring Program Outcomes And Our Impact

- Client and Caregiver Feedback

As part of our commitment to being youth-centered and family-led, youth and caregivers are invited to share their experiences with VIP through the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (HVIP-CSQ). Completed after program participation, this tool collects information to inform our on-going program improvement efforts. Impressively, on average, they rate VIP services at 9.1 out of 10 and more than three-quarters report that VIP met most or all of their needs.

“CHOP VIP's [case managers] gave us the best possible treatment, care and follow-up possible. They each helped us deal with and overcome the complexities of the legal system and at the same time helped us heal through trauma therapy. Overall, these providers helped us attain post-traumatic growth. What we learned through CHOP VIP will continue to help us.” - Caregiver

“Everything about this program was great and helped made me feel better as a person and my situation so I am very grateful :).” -Youth

- Youth and Client Stories

Former VIP clients Chedaya and Dee Dee tell their personal stories of participating in VIP.

Chedaya

Dee-Dee

Select VIP Research and Evaluation Projects

- Addressing Community Violence-related Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Children

Study PI: Joel Fein, MD, MPH

Study Team: Steve Berkowitz, MD; Nancy Kassam-Adams, PhD; Rachel Myers, PhD, MS; Guy Diamond, PhD; Justine Shults, PhD; Laura Vega, DSW; Stephanie Garcia, MPH

Study Sponsor: NIH/NICHD

Project Goals: We are conducting this prospective, randomized control trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the 5-8 session Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention (CFTSI) provided soon after a physically violent traumatic event. The study will continue to enroll youth and families through 2022. We are evaluating whether CFTSI, provided in addition to VIP services, can produce significant and sustained reduction in posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) among youth aged 8-18 years.

- Formative Evaluation of a Pediatric Hospital-based Violence Intervention Program

Study PI: Rachel Myers, PhD, MS

Study Team: Nancy Kassam-Adams, PhD; Joel Fein, MD, MPH; Laura Vega, DSW; Hillary Kapa, MPH

Study Sponsor: National Institute of Justice

Project Goals: The objective of this project is to rigorously describe the components and outcomes of the victim service program offered by the CHOP VIP. Through this study, we will develop and define the tools and resources needed to support program implementation, including possible measure of program fidelity and key outcome metrics, defined with diverse stakeholder input. Additionally, this grant will develop tools to support trauma informed supervision for pediatrics HVIPs.

- Mapping Case Management Activities to Support Implementation and Fidelity of a Pediatric Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program

This study conducted a retrospective, qualitative analysis of over 2,000 patient encounter notes from the CHOP VIP, which were written by program staff to document the case management care provided to patients and their families. We mapped these case management activities to 62 discrete recovery goals across 12 need-specific domains, related to areas of physical and psychosocial well-being. These evidence-informed tools to guide case management may enhance fidelity of program delivery and provide clarity around community-focused case management.

- Assessing the Intersection of Bullying and Physical Violence among Patients Seeking Primary Care

Study PI: Rachel Myers, PhD, MS

Study Team: Tracy Waasdorp, PhD; Hillary Kapa, MPH

Study Sponsor: Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Foerderer Award

Project Goals: The objective of this study is to describe the burden of pediatric injuries treated in primary care following intentional interpersonal violence and the intersection between bullying and physical victimization to inform prevention and intervention efforts.

- Seasonal Variation of Assault Victimization in a Pediatric Center and its Association with the Academic School Calendar

Study PI: Ashlee Murray, MD, MPH

Study Team: Joel Fein, MD, MPH; Rachel Myers, PhD, MS

Project Goals: The purpose of this study is to describe the temporal variation in assault injuries presenting to a single, urban pediatric ED, and to test the hypothesis that there is an association between the incidence of pediatric assault victimization and the academic calendar.

- Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

Project Goals: Few standardized tools exist to capture experiences of clients participating in hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIP) to ensure program relevance and responsiveness. As a quality improvement initiative, we developed a tool to measure client satisfaction utilizing feedback from youth and caregivers participating in the VIP at CHOP. Created with client feedback, our 12- item tool, the Pediatric HVIP Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), systematizes collection of HVIP client satisfaction and supports the inclusion of client and caregiver voices in quality improvement and evaluation efforts. At present, the VIP at CHOP administers the CSQ to all clients and caregivers at the conclusion of their services as part of ongoing program evaluation.

- Generating a Core Set of Outcomes for Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs

The post-injury needs of someone who has been violently assaulted are varied and complex. To reduce future re-injuries, hospital-based violence intervention programs (HVIPs), including CHOP’s Violence Intervention Program, provide violently injured individuals with support and case management following discharge from the hospital. This study addresses the types of outcomes these programs can and should look to achieve for their clients to create safety in the aftermath of violent injury.

- The Psychosocial Needs of Adolescent Males Following Interpersonal Assault

This study found that among 49 young men of color ages 12-17 who voluntarily enrolled in CHOP’s VIP program from 2012-2016, the vast majority (89%) self-identified a need for mental health care, with specific goals including therapy, psychiatric evaluation, and suicide safety planning. Adolescent boys also identified legal, education/school, employment, medical, and safety needs.

- Exploring Program Implementation of a US Pediatric Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Program by Injury Mechanism

To date, there has been insufficient examination of who Hospital-Based Violence Intervention Programs (HVIPs) serve and how programs are implemented, especially among pediatric patients. This study sought to describe the implementation of a pediatric HVIP and examine the relationships between HVIP implementation metrics and mechanism of injury (firearm vs. non-firearm). We observed similarities in recovery need domains, retention, and program outputs across clients with varying injury mechanisms, suggesting the acceptability of and utility of the HVIP model for young people with diverse injury types.

Resources for VIP Families

- VIP Brochures

Learn more about VIP services by reading our brochure in English or Spanish.

- Violence Prevention Resources

Access information about support services related to exposure to violence.

Funding Acknowledgements

- VIP receives funding from various sources to sustain our services, including:

Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency: VIP is supported by PCCD Subgrant #2022-VF-05-40204-2, awarded by the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency (PCCD). The awarded funds originate with the Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice or U.S. Department of Education or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. VIP is also supported by PCCD Subgrant #s 2024-VI-VI-46935 and 2022-CV-VI 39773 . The opinions, findings and conclusions expressed within this publication/program/exhibition are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of PCCD or applicable federal agency.

* We are proud to partner with many community-based programs to support the comprehensive needs identified by youth and families. This holistic approach aligns with our desire to enhance the overall health and well-being of children and families within Philadelphia.